A poignant discovery...and then some.

(part I)

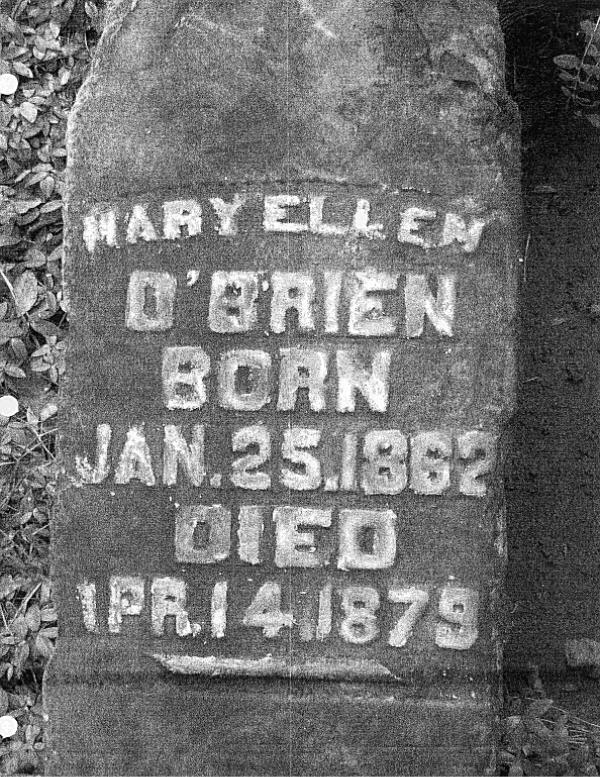

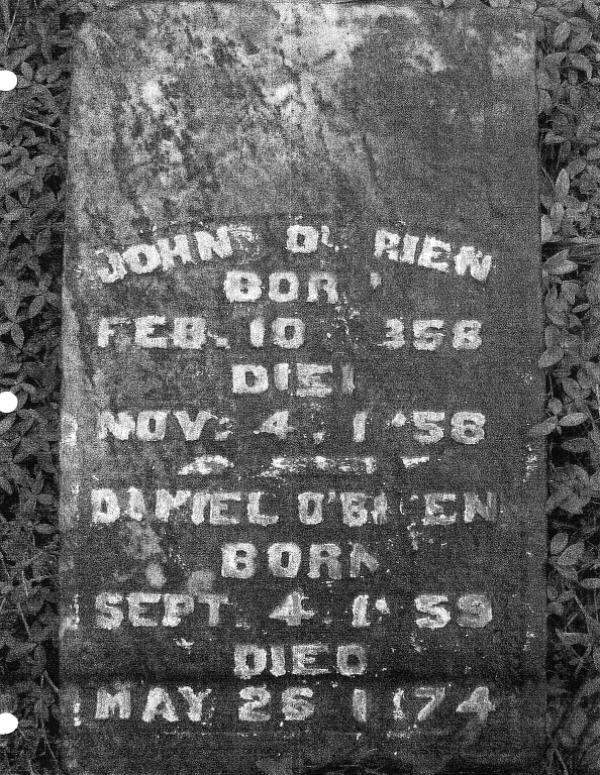

When Linda and I were up in the Copper Country in the fall of 2006, we did a little poking around just because for, among other things, information about ill-starred Mary Ellen O'Brien, Grandpa's oldest sister who died when M.E. was just a year-and-a-half. As you can see by the above gravestone, Mary Ellen herself was quite young, just 17-years-old. I'd seen her name on the family tree for years and wondered about her life and her early death. However, she has always been a familial enigma, with virtually nothing known about her other than she was the first girl and fourth child born to Patrick and Mary O'Brien.

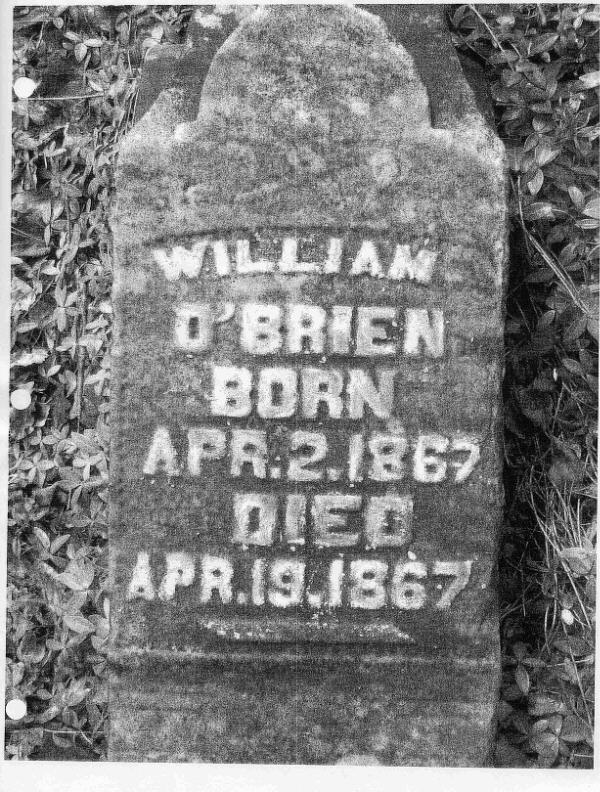

All told, Pat and Mary had nine children. The first four were born in Boston, and the last five were born in the Keweenaw. Sadly, those first four children would all die prematurely, two in infancy in Boston (William and John); one in a mining accident at Cliff Mine at age 14 or 15 (Daniel); and the above-noted Mary Ellen.

This tragic fact -- four children lost -- must have haunted Pat and Mary for their entire lives. If you were to take a moment to ponder how you would feel losing even one child, you might get a small sense of the enormity of their anguish.

In any case, we learned about Mary Ellen's burial site purely by chance while visiting the Michigan Tech Library in Houghton, MI. We had asked Eric Nordquist, the archivist (a fancy name for librarian), how we might find Mary Ellen's obituary. Probably never happen, he informed us, as death notices were rarely published for "ordinary" people back then and doctors weren't yet obliged to report deaths.

As a result, dead people could easily fall through the proverbial cracks, particularly in a place like the Keweenaw. In the early days, the Peninsula was largely made up of transient communities that were tied to the success or more likely, failure of the various mining companies. People had by necessity to keep on the move to keep employed.

Okay, then, with no obituary or death record to count on, we then asked how we could find out where she's buried, figuring that ANY discovery pertaining to this long-forgotten soul -- dead now for these 129 years -- would be major. At that question, Eric replied, "Well, you could ask Peg." He then motioned off across the room to a middle-aged woman sitting at her laptop, pecking away.

***

Besides her day job as Patient Financial Services Supervisor at Keweenaw Memorial Hospital in Laurium, Peg Niedholt is also a professional genealogist. In that capacity, one of her current projects involves going into abandoned cemeteries in the Copper Country and recording the information found on headstones, photographing the stones, and ultimately, along with her colleagues in the Houghton-Keweenaw Genealogical Society, restoring those cemeteries, when finances permitted.

When I asked her if she had ever come across a Mary Ellen O'Brien, her eyes widened in astonishment -- she had just typed that name into the database! She beckoned us over to look at the spreadsheet on her computer screen and then pulled out a binder and showed us the photo she'd taken of the stone (the one shown above), handing us a copy to keep. She also gave us xeroxes of the inscriptions found on the stones of other O'Briens she'd discovered there: William, John, and Daniel.

Of course, I was flabbergasted at hearing all of this within a minute or two of meeting Peg -- She had just named Pat and Mary's first four children, the ones, you remember, who all died young.

Going far beyond the call of duty, Peg even volunteered to take us to the old Hecla Cemetery in Laurium and show us Mary Ellen's gravesite, which she had found just a day or two before. Talk about timing.

The next morning, true to her word, Peg took a break from her work at the hospital and delivered us to the cemetery.

Hecla cemetery is in absolute shambles with few gravestones actually standing straight up. It has been abandoned and untended for decades, a microcosm of the Keweenaw itself with its ghost towns, moldering buildings, and faded memories of yesteryear. With a hand-drawn schematic for reference, Peg took us up this overgrown path and down that one until stopping, she pointed out Mary Ellen's stone, which lay tumbled onto its side.

Then, having so graciously gotten us here but needing to return to work, Peg handed us a copy of her map and indicated where we'd find the other O'Briens, including one right at Mary Ellen's grave site. We thanked Peg profusely for her kindness, still quite dumbfounded by our luck at running into her the evening before.

The whole experience of finding this gravestone was touching enough in its own right because now, for me at least, Mary Ellen was more than simply a name typed into a genealogical chart... Here she lay -- poor, unfortunate soul that she'd been -- right before us, and this fact made her existence somehow more tangible to me. She was the sister of my grandfather -- a very direct link -- left behind seemingly for good when the family migrated to Detroit in 1911. And now, by sheer luck, we'd come upon her.

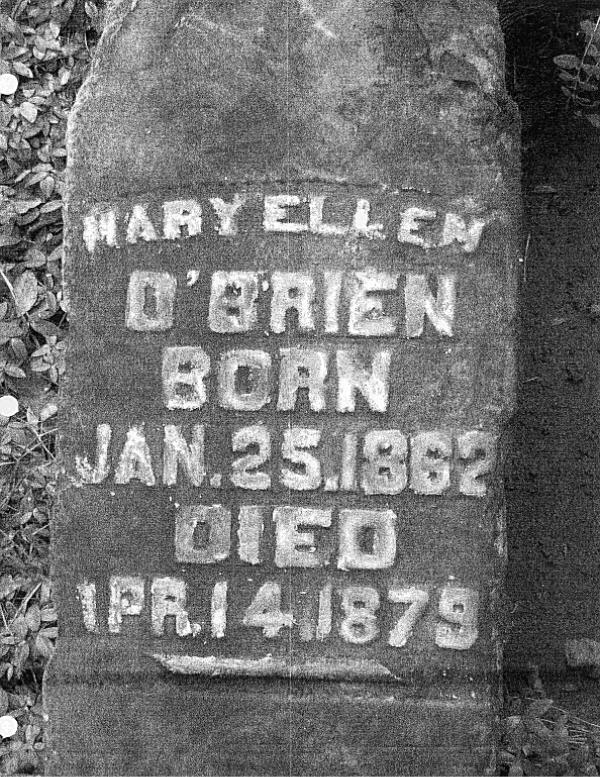

We bent down and examined Mary Ellen's inscription, which was still clear and easily distinguishable. Then, we focused on the other inscription, noted on the map that Peg had given us. This one was on the side adjacent to Mary Ellen's, facing up. And this is when the plot thickened: It was for William O'Brien who, according to the stone, lived just 17 days, from April 2 to April 19, 1867.

Mary Ellen O'Brien's tombstone (above), knocked over by vandals or simply toppled by time, contains both her inscription (on the side facing us in this photo) and an inscription for William O'Brien (on top, facing up), an infant who lived just 17 days.

Although the year carved into the stone for young William is 1867, we believe that this is in error and should be 1857 (at least, all the information we have on the subject indicates that fact).

Patrick and Mary O'Brien's first two children -- William and John -- died in infancy in Boston and, it is assumed, were buried there in pauper's graves without stones. This inscription might well represent the belated recognition of the life and death of their late son, and they tacked it onto Mary Ellen's tombstone to finally achieve that recognition (and because it was an inexpensive solution).

As you'll soon see, they did precisely the same thing with their two other Boston-born children, John and Daniel, both of whom died prematurely, John, as mentioned, in infancy in Boston and Daniel at age 14 in a mining accident in the Keweenaw. Their headstone is also in the Hecla Cemetery, but that we found it is somewhat of a miracle....WOM

An amazing coincidence? Or not?

(part III)

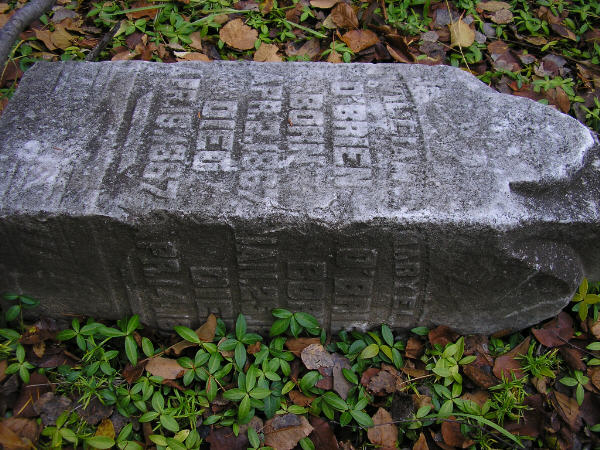

Peg led us to Mary Ellen's grave, but then had to get back to the hospital, so Linda and I were on our own when we set out to find this stone. In our opinion, it represents the final resting place -- or at least, acknowledgement that they once existed -- of John and Daniel O'Brien. The above representation of their headstone is deceiving. We learned that one of the tricks of a genealogist's trade as she gathers information from a tombstone is to rub chalk over its surface to bring out the inscriptions. That's how Peg got such a good photo. Without the chalk, the letters and numbers, so easily readable above, are almost nonexistent.

NOTE: This is where the "Reader's Digest" version of the story ends. To continue, click on the link just below which will take you to the unabridged text. You can begin reading at the beginning or scroll down and pick up the thread where the above post leaves off...

Click here to read the entire unedited story of the discovery of the graves of the four O'Briens.